The prominence of ‘start-up’ culture in the zeitgeist of today, as well as the ubiquity of technology, can give the impression that innovation is a straightforward, predictable process. ‘Entrepreneurs’ study for a computer science degree (maybe they drop out two years in), get some funding from a venture capitalist, and then come up with some world-changing piece of technology.

Things aren’t so simple. If you look back at the past couple of centuries, many of the more ground-breaking pieces of technology have been discovered or developed fairly randomly, often by people with no training in the field they were working in.

The power loom, for example, was invented by Anglican priest and hobbyist engineer Edmund Cartwright in the 1780s. About 150 years later, penicillin – arguably the most life-changing product of the past century – was discovered accidentally by Alexander Fleming. More recently, the messaging software Slack was created as a side project by a group of video game developers, who needed a tool to communicate with each other when remote working. The video game failed but the messaging software was sold for $27.7bn last year.

In short, there is no clear cause and effect when it comes to developing new technologies, making it hard to predict who will be responsible for producing them. For investors, this is an annoying situation to be in as it means investing in the next piece of ground-breaking tech is very hard to do. Venture capital is arguably the best approach to this conundrum. Taking lots of small bets on early stage, high risk companies, with massive pay-offs means you have a better chance of getting exposure to these sorts of unpredictable breakthroughs.

What arguably changes this dynamic, however, is some sort of necessity. As the composer Leonard Bernstein once quipped, “to achieve great things, two things are needed; a plan, and not quite enough time.” We saw this during the pandemic when medical companies were able to create vaccines in a remarkably short period of time. It is hard to imagine them having done so had it not been for the sense of necessity motivating their work.

Although they’re not as pressing relative to the development of a vaccine, there are still plenty of areas for investors to consider that may see necessity leading to innovation.

One country that arguably shows this is the case is Japan. The country’s well known demographic problems mean there has been a growing need to automate large parts of the economy. At the start of 2015, the government even introduced the ‘Robot Revolution Initiative’ to try and make Japan a world leader in robotics.

That was probably already the case (maybe it was the robots that caused the demographic problem, rather than the other way around), given that companies in the country consistently produce over half of the globe’s industrial robots on an annual basis.

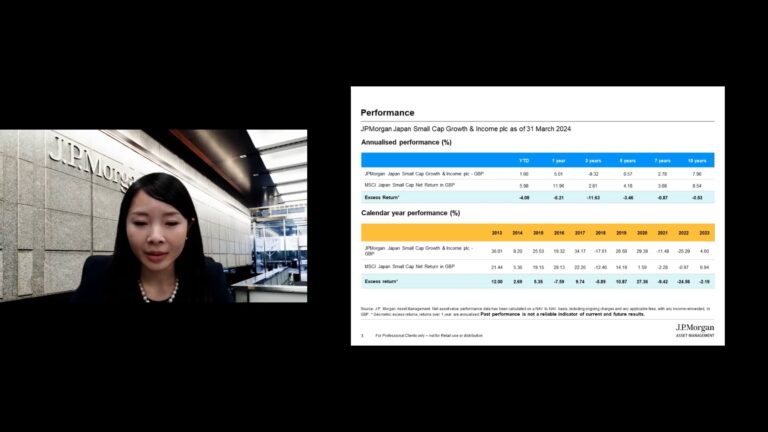

One trust that looks to tap into this area is JPMorgan Japan Small Cap Growth & Income (JSGI). The trust offers access to many of the companies hoping to cater to the so-called ‘New Japan’ economy, which looks to be comprised in part of businesses active in automation, environmental solutions, and digitization. That latter point may sound generic, but there are many areas, cloud computing being a notable one, where Japanese companies have lagged massively behind their western peers.

Of course, this doesn’t mean the companies JSGI invests in are guaranteed to succeed. But identifying areas where necessity is likely to lead to innovation seems like a better option than scouring the world and trying to figure out who the next Bill Gates is going to be.

Japan income fund, JPMorgan Japan Small Cap Growth & Income plc (LON:JSGI / JSGI.L), targets Japan income without compromising on Japanese growth opportunities. This Japan fund is an income investing opportunity that gives investors access to a diverse and fast growing sector managed by local managers. The Investment Trust offers a regular quarterly income without compromising on Japanese growth opportunities, by paying a higher dividend funded part by capital reserves as well as revenue returns.

Kepler Trust Intelligence is written and published by the Investment Companies team at Kepler Partners